To be desirable is currency. To desire is liability.

Between semen retention and self-tracking, the modern subject has turned erotic energy into an economic asset. But in our devotion to control, have we traded vitality for efficiency?

Earlier this year, at a brand dinner, I found myself seated next to a man midway through 75 Hard. Between bites of salad, he preached the gospel of dopamine detoxes and 5 a.m. wake-ups. Then, mid-sentence - somewhere between cold plunges and Andrew Huberman - he told me he hadn’t ejaculated in over three months. To clarify: he has had sex with his girlfriend. He just doesn’t let himself finish. He was the second man to tell me this year.

Apparently, the idea came from Think and Grow Rich. Published in 1937, the self-help relic claims to reverse-engineer greatness through sixteen laws of success drawn from the habits of history’s so-called Great Men. The tenth, The Mystery of Sex Transmutation, insists that sexual energy is one of the most powerful forces in existence, and that a man who can channel it into ambition will be unstoppable. According to author Napoleon Hill, Abraham Lincoln was particularly skilled at this.

Now, I doubt President Lincoln was observing No Nut November, but it is very telling of our time that the NoFap community has rebranded the book as a manifesto for withholding. Men like my dinner companion have become high priests of abstinence-as-advancement, alchemising libido into productivity, hunger into hustle and semen into synergy. It’s all very Silicon Valley Tantra.

In fairness, though, everyone seems to be doing some version of this. We’re living in an era of extreme want - to be hotter, more locked in, more aura-maxxed - while simultaneously in an age of extreme deprivation. Celery juice at sunrise. GLP-1 at lunch. "Low dopamine mornings and high-protein evenings. It’s not asceticism; the goal isn’t enlightenment. It’s just a way to raise our market value.

Most of our improvement trends can be boiled down to this: everyone wants to be wanted, but no one wants to actually want. If desirability is a currency, then to desire is a liability. Nearly everything feels calibrated toward being chosen, though for what exactly, I’m not sure anymore. A follow on Instagram? A date with a better swag ratio than your ex? Life has begun to feel like an endless casting call for desirability, except no one knows who’s behind the camera or what role we’re even auditioning for.

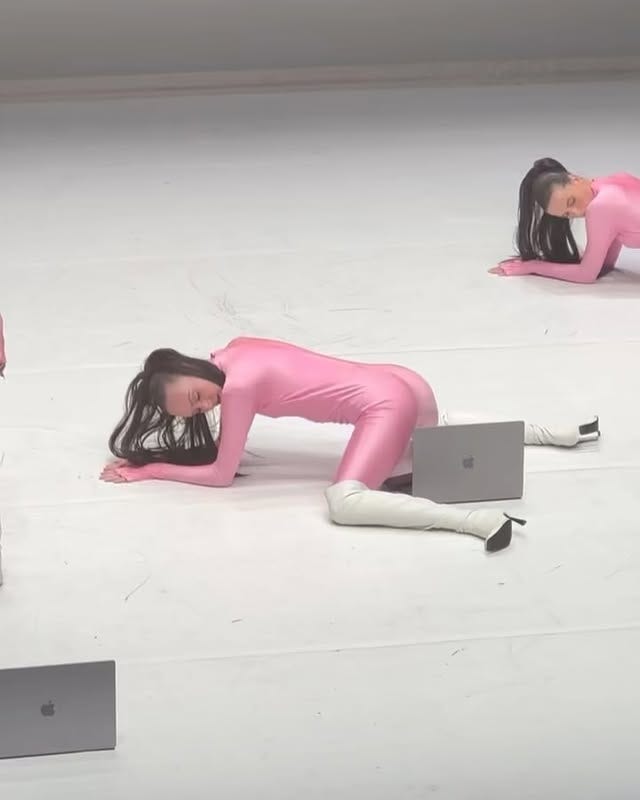

This new strain of self-alienation has bloomed against a pornified backdrop, where exhibitionism masquerades as empowerment and is rewarded as long as the body in question fits neatly within the algorithm’s margins. Sabrina Carpenter is the current patron saint of sex even though she looks like a Barbie doll with no private parts. Everything is suggestive, but nothing actually suggests anything that looks pleasurable.

I’ve been thinking about this ever since Marina Abramović announced her new show, Balkan Erotic Epic, a four-hour ritual of thirteen scenes and seventy performers, rooted in Balkan folklore and ancestral rites. Abramović said she’s “determined to show the erotic as a portal into cycles of life, not as commercially sexual,” which feels like exactly what we’re missing.

As a culture, we no longer understand the erotic. We’ve stripped it for parts, degraded it into porn, profanity and performance until even saying the word feels faintly indecent. But to feel erotic, in its oldest sense, is to be overtaken by life: that blinding heat that rises when you’re so present you almost dissolve. It’s the pulse that makes art possible, conversation magnetic. Call it flow state. Call it Eros.

The problem is, we’ve built a culture designed to resist that kind of surrender. We’re too busy managing ourselves to be moved by anything, deferring gratification to some future, more optimised self who is probably too emotionally regulated to feel much at all.

Our bodies are not objects to be monitored, but living vessels through which we experience and connect with the world. But most of our encounters now happen through screens, so I guess it’s easy to see how we’ve rationalised Eros to death, until the thing that was meant to make us feel alive mostly just makes us feel… efficient. The great irony, of course, is that by cutting ourselves off from it, we condemn ourselves to mediocrity. Worse, this fragmentation of self leaves us increasingly susceptible to exploitation by systems and people indifferent to our actual interests. Disembodiment breeds compliance; when we abandon our own desires, it becomes easy for others to script them for us.

Eros in the age of optimisation

The word erotic has been domesticated over time, narrowed to mean something you’d probably search for in private. But it comes from Eros, one of the oldest Greek gods, who, before he was Cupid with his bow, was born from Chaos itself. In the earliest stories, Eros wasn’t about romance or lust the way we think of it now. Instead he was the universe’s first stirring, the pulse that pulled order out of disorder and made matter come together. Less a feeling than a force, the will that draws atoms into pattern and makes something out of nothing.

Throughout history, thinkers from Freud to Audre Lorde have understood Eros as a kind of internal voltage. For Freud, Eros was the life instinct, the drive that pulls us toward connection and creation. For Lorde, it’s what wakes us up from numbness. “For once we begin to feel deeply all aspects of our lives,” she wrote in her seminal Uses of the Erotic essay, “we begin to demand from ourselves and from our life-pursuits that they feel in accordance with that joy which we know ourselves to be capable of.”

In both myth and theory, Eros is the same force: the spark that brings aliveness out of inertia. To live erotically is to stay attuned to that rhythm, to let the energy that animates the world also animate you. But that kind of vitality resists management, which is precisely why the modern world fears it.

Our long slide away from Eros has been happening for centuries. Georges Bataille thought it was the inevitable price of civilisation. Animals, he wrote in his 1957 book Eroticism, live in continuity with the world, never standing apart from what they are in. They eat, sleep, mate, die without rupture between being and doing. Humans, by contrast, live in discontinuity. In creating tools, we created subjects and objects, and the self was born somewhere in that divide: the one who acts and the thing acted upon. Progress gave us stability but it also peeled us away from the world. “We are discontinuous beings,” Bataille wrote, “individuals who perish in isolation in the midst of an incomprehensible adventure, but we yearn for our lost continuity. We find the state of affairs that binds us to our random and ephemeral individuality hard to bear”. Our individuality - the thing we fetishise - is also our torment. We crave the feeling of being waves among other waves, even as we build systems to prevent exactly that.

There are only two ways back to that continuity: death and the erotic, which, as the French remind us by calling orgasm la petite mort (the small death), are more alike than we’d like to think. Read alongside Freud, eroticism becomes a model for living: what Bataille called “assenting to life up to the point of death.” Sex is one route, death is another, but so is losing yourself in dance, devotion, art, awe, good conversation - anything that momentarily dissolves the boundary between you and the world.

However, if Bataille’s tragedy was that civilisation severed us from continuity, ours is that we have built machines to institutionalise the severance. We no longer stand apart from the world; we scroll through it. The subject and the object have been supplanted by the user and the interface, and what was once an encounter has become an evaluation measured in metrics. This system teaches us not how to meet others fully, but to hover at a safe distance, treating every interaction like a mental tabulation. Am I hotter? Funnier? More stable? Should I be drinking chlorophyll water too?

It’s easy to mistake this hyper-self-awareness for self-knowledge. But the more we monitor ourselves, the less we seem to truly know ourselves. The erotic is where you’re absorbed into people, places, meals, music, art, museums. Not assessing them from afar for how they’ll play in your performance of self online.

“Eros and depression are opposites. Eros pulls the subject out of itself, toward the Other. Depression, in contrast, plunges the subject into itself. Today’s narcissistic “achievement-subject” seeks out success above all. Finding success validates the One through the Other. Thereby, the Other is robbed of otherness and degrades into a mirror of the One - a mirror affirming the latter’s image.”

Byung-Chul Han, The Agony of Eros

And yet, I get it. The world’s a mess, and control feels like the last safe drug. It’s easier to tweak your skin-care routine than to face the possibility that no amount of retinol will fix the deeper rot. But control is a fragile high. It wears off the second something unpredictable happens.

Eros doesn’t work like that. Like the force that made it, it can feel a bit like chaos — the ecstatic undoing of the self, not the obsession with shaping it. It asks you to loosen your grip, to risk being moved - not just emotionally, but deeper into unguarded parts of yourself you’ve learned to shut off. And that’s terrifying, because control promises safety, even if it never delivers. In an age that rewards optimisation, Eros acts as an insurgency. It’s what happens when you stop tracking your steps and start noticing where you are actually walking to.

Audre Lorde called the erotic “an internal sense of satisfaction to which, once we have experienced it, we know we can aspire. For having experienced the fullness of this depth of feeling and recognising its power, in honour and self-respect we can require no less of ourselves.” That’s my favourite way to think about eroticism: as self-possession in the most literal sense. To feel yourself deeply is to become harder to manipulate. You can’t sell much to someone who already feels whole, which is why we’re taught to stay slightly hungry all the time, whether it be for love, for validation or for a version of ourselves that can be improved just a bit more.

How to cultivate more Eros

1. Courting slowness.

Speed is the enemy of depth. We move through life like we’re late for something no one ever told us the start time of. “How are you?” “So busy.” God, that phrase makes me want to walk into traffic.

This constant rush also messes with our sense of time. Time isn’t fixed; it’s elastic. It stretches or snaps depending on how much of you is actually present. Thirty minutes on a treadmill feels like an eternity; thirty minutes on your phone vanishes before you even notice. In one, you’re in your body; in the other, you’re kind of suspended, scrolling the surface of life instead of being in it. That difference, that gap between time spent and time felt is Eros’ whole playground.

Psychedelics make this obvious. Anyone who’s taken shrooms knows that time stops behaving like time. How it stretches out, how it gives itself back to you when the warm fuzz and fluid colours kick in. Slowness has become a cursed word, but if you’re living properly, everything should unfold in that deep-time zone where things ooze and stretch instead of blur. The alternative is that familiar hunch over the laptop, stomach knotted, racing to tick off as many to-dos as possible before you remember that most of them don’t actually matter.

2. Protecting your attention.

The erotic withers under surveillance, especially self-surveillance. Create unmonitored space. Mystery is oxygen for desire.

3. Embracing sincerity.

Eros hates irony. You can’t indulge with the world if you’re too busy pretending you don’t care. We’ve built a whole culture around deflection but erotic aliveness requires exposure.

Living below the neck.

We’ve become a species of floating heads - all brain, no body. Most of us live like we’re piloting a machine from the control room rather than actually in it. But the erotic lives in the flesh. You don’t have to do yoga or breath work or whatever’s trending this week; you just have to remember you have a body.

Loved the idea that the eroticism is “what happens when you stop tracking your steps and start noticing where you are actually walking to.”

Led me to think about the huge rise in wearable tech that is rarely used to create real lifestyle changes. In the very pursuit of getting closer to our bodies, we’ve completely detached ourselves from feeling. Do I need my watch to tell me I’ve had a bad night sleep or can I just listen to my body?

I appreciated this take a lot. I see this a lot with the whole "I don't chase" rhetoric. Not because we should be desperate doormats, but if no one pursues, if no one allows themselves to be a bit silly, if no one desires, how can everyone else be desireD?

Out of nowhere, we all want to be the ones chosen but never to choose. To initiate. So quick to "set boundaries" even where there's nothing toxic or harmful going on. It's like wanting to have the upper hand all the time. Everyone wants the other person to text first, for example. So no one texts anyone and we're all sad and lonely. I'm exaggerating, clearly. But it's a tendency I've seen too. Trying so hard to be cool that we forget to live. Because life is rarely that cool and detached. Life requires you to go and make a fool of yourself sometimes.

But I'm interested in your take of using the body more and not just the mind. What do you think about situations in which rationality says one thing, and the body another?