The collapse of cool

Once a way to sidestep the system, cool now feeds it. We traded autonomy for aesthetics - no wonder the culture's cooked.

Cool is one of those slippery concepts you’re not supposed to interrogate too closely. Everyone wants it, but it’s not cool to admit that you do. It’s a status you can’t claim for yourself without losing it. “Cool” defies definition by design - if you have to ask what it is, that’s proof you don’t have it.

That vagueness also made it easy to co-opt. Because we never agreed on exactly what “cool” is - or examined why we even want it - we left it undefended, a commons plundered first by Madison Avenue and now by the algorithm. Born as an unspoken language, it’s been unpacked and weaponised into a coercive tool, crafted to make us covet things we don’t need and aspire to ideals with no real bearing on the quality of our lives.

We want it so badly we make decisions that defy our own logic: chasing products and lifestyles not for their utility but for their proximity to the idea of cool. And in that pursuit, we’ve drained the cool of the very cultural richness that once made it worth having. What was once an act of being has become an act of buying, and in seeking it so relentlessly, we’ve extracted it from the culture entirely.

Which is how we arrived at Brain Rot Summer - as Business Insider christened it - where, in Amanda Hoover’s words, “the biggest vibe is the lack of actual vibes.” The cultural bloodstream is still moving, but what’s coursing through it are micro doses of chaos: AI-generated bunny videos, the jarring Jet2 Holiday jingle, bot-lickers sending themselves into Chat GPT-induced psychosis, £600 flip-flops that prove marketing can turn pool noodle material into a status symbol.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Unlike summers past, there’s no big shot of adrenaline to send everyone sprinting in the same direction. Hoover points out that we’re halfway through August and still have no song of the summer or dominating colour. Last year was Brat summer. The year before, Barbie pink. Now the nearest thing to monoculture we’ve seen is a collective meltdown over Sydney Sweeney’s American Eagle ad – less a unifying vibe than a mass anxiety attack.

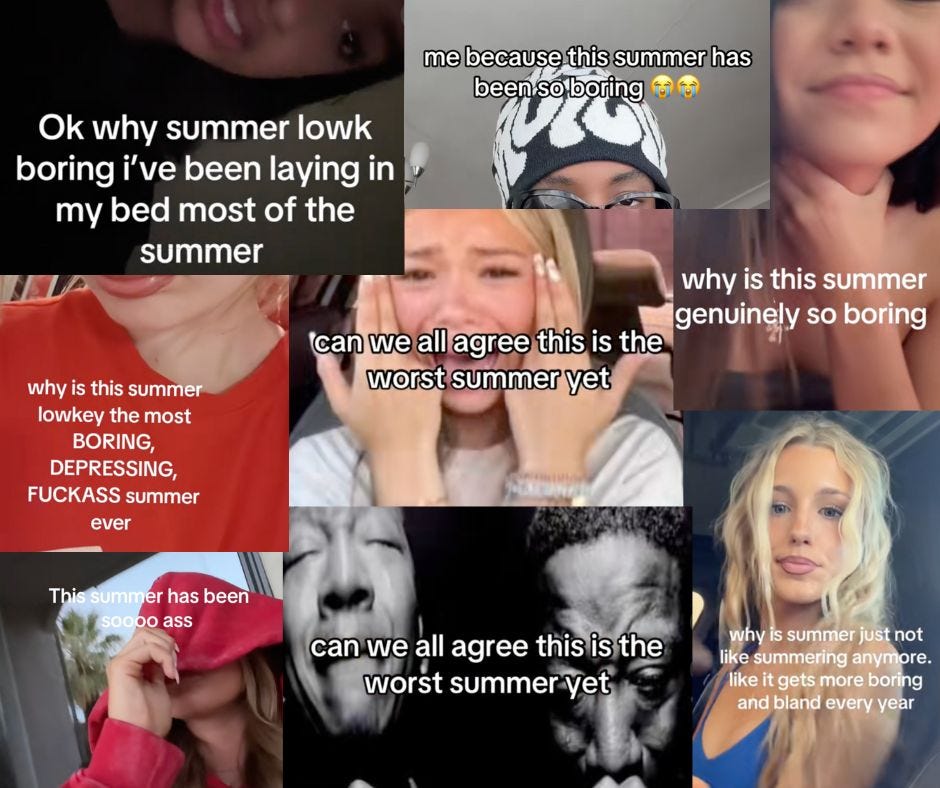

And if cool has always implied a good time, this summer has delivered anything but. Instead it’s been the Summer of the Crash Out - collective burnout manifesting in petty Instagram fights and rage-scrolling political news. There’s a simmering anger under everything - unbearable climate heat waves, Trump dominating the news cycle with nonsensical outbursts, reproductive rights rolled back - and the sense that we’ve hit the upper limit of how much stimulation and outrage we can metabolise before we flatline. No surprise, then, as Casey Lewis noted in her Substack After School, that TikTok is full of people lamenting that “this summer lowkey sucks”.

The vibes aren’t just off, they’re completely shot to shit. Cool is in ruins. But to rebuild it, we need to excavate the foundations.

The birth of “cool”

According to Todd Pezzuti, Caleb Warren and Jinjie Chen in their study Cool People, the earliest roots of cool lie in the African diaspora, in West African ideas like itutu (Yoruba for “coolness”), which refers to a state of spiritual composure and grace under pressure. Confronting the brutal realities of slavery and Jim Crow, African Americans reshaped this ideal into a survival strategy, preserving dignity and self-possession in a society determined to strip them away.

By the mid-20th century, jazz transformed this sensibility into a cultural form. Built on choices made in real time, jazz demanded a balance of discipline and improvisation. For Black artists, exercising that freedom in tightly controlled, often hostile spaces was a radical act. Touring meant segregated venues, unsafe travel and even basic needs like food and lodging denied. Within those constraints, musicians claimed authority in the music itself, deciding how a song would bend or break, when to step forward or pull back.

Jazz in this moment was the first modern embodiment of cool – a demonstration that cultural autonomy could be generated from outside the dominant hierarchy. That kind of defiance (the refusal to be defined entirely by an oppressive system) is both historically specific and fundamentally human. Across cultures and eras, people have sought ways to claim autonomy when faced with rigid control, whether by force or by convention. We all have, buried in us, an impulse to resist subordination.

Steven Quartz and Anette Asp, in Cool: How the Brain’s Hidden Quest for Cool Drives Our Economy and Shapes Our World, place this impulse within the larger framework of human status behaviour. They describe two powerful drives: the “status instinct”, which pushes us to compete for position within an existing hierarchy and the “rebel instinct”, an aversion to subordination so strong it appears even in other primates. Where the status instinct climbs, the rebel instinct sidesteps the ladder entirely - sometimes inventing new measures of worth altogether.

It’s easier to think of it like this. For most of history, status operated as a rigid zero-sum pyramid: few places at the top, many at the bottom, and movement upward usually requiring someone else’s fall. The Gilded Age industrialists codified this into a culture obsessed with wealth displays, social climbing and a narrow set of prestige markers.

But by the mid-20th century, conditions were shifting. In postwar America, rising incomes meant more people could compete in the old status game – but the game was still structurally rigged. Racial and gender discrimination, institutional gatekeeping and a suffocating culture of conformity kept power concentrated at the top. In that climate, the rebel instinct had fertile ground.

Come the 1950s and ’60s, “rebel cool” had crystallised into a visible set of countercultural identities – beatniks in black polo-necks and berets, hippies in flowing fabrics and communes, Yippies staging satirical street protest theatre. Drawing on roots in Black jazz culture and the Beat Generation’s literary revolt, rebel cool fused artistic experimentation, anti-consumerism and a rejection of state authority into a coherent style of resistance. It was coded and exclusive: dress, slang, music and mannerisms acted as in-group signals, allowing adherents to claim standing outside the traditional prestige game. For hippies, that meant turning away from materialism and the Vietnam War in favour of peace and spiritual exploration; for Yippies, it meant mocking power with acts such as attempting to “levitate” the Pentagon. These subcultures diversified the very idea of status – proving you could command respect through autonomy, authenticity and refusal to “sell out”, rather than by imitating the mainstream.

The commodification of “cool”

The energy that had once fuelled walkouts, underground zines and garage bands was soon rerouted. By the late 1960s, the advertising industry had adjusted its frequency, tuning into the language of dissent. Youth rebellion, once allergic to commerce, became a tonal palette for selling everything from blue jeans to cologne.

Thomas Frank, in The Conquest of Cool, argues that “hip capitalism” emerged as companies harnessed satire, tongue-in-cheek detachment and revolutionary rhetoric to sell products as emblems of radical self-expression. As Frank observes, many in business “imagined the counterculture not as an enemy to be undermined or a threat to consumer culture but as a hopeful sign, a symbolic ally in their own struggles against the mountains of dead-weight procedure and hierarchy.” In effect, difference - rather than conformity - became the new selling point, and slogans born in student sit-ins began turning up in print campaigns and shop windows.

The “rebel instinct” that Quartz and Asp frame as an evolutionary defence against subordination entered a feedback loop with consumer capitalism. And we humans, with our tendency to take the shortcut, soon got high on the promise of buying into versions of cool that had once been hard to access. No longer confined to the vertical climb of old status systems, aspiration could now be sold laterally, across an ever-expanding grid of niches.

Within a decade, the shapes of resistance had been flattened into market segments. The leather jacket carried by bikers into roadhouse bars now sat under department store lighting. Punk’s safety pins and sneer came printed on mass-produced T-shirts. Hip-hop’s regional dress codes, designed as acts of local self-definition, were reconstructed for suburban malls. Advertising no longer positioned itself as the voice of the majority; it began to speak in the cadences of refusal, selling the sensation of being outside the mainstream while ensuring every purchase kept you firmly inside it.

The blueprint Madison Avenue perfected in the late 20th century - identifying the symbols of dissent, packaging them and selling them back to us as identity that easily signalled to others our rebel cool status – did not vanish with the decline of print ads and TV spots. It migrated, accelerated and became participatory. By the 21st century, social media had turned the old cycle of co-optation into a near-instant reflex. Trends that once travelled through underground networks over months now rise and vanish within days. And with it, the feed collapses the gap between creation and commodification; cool is no longer tied to scarcity or authenticity, only to visibility. And visibility itself becomes the currency.

Take 2024’s Barbiecore. Warner Bros. staged a $150 million global campaign - larger than the budget of the film, notes Business Insider’s Hoover - that saturated every corner of the culture, from high-fashion capsules to themed Airbnb rentals. Social media frames such moments as bottom-up phenomena, viral because “the people” made them so. But what dominates the feed is often powered by label budgets, PR calendars, influencer seeding and brand partnerships. The algorithm has become the new Madison Avenue, orchestrating participation rather than simply selling products. Buying in doesn’t always require a purchase; posting your own Barbiecore TikTok is enough.

It helps to think of the loop like this:

A new thing arrives dressed as a reactionary force. In the case of Barbie, it channels the rebel instinct into the reclamation of girlhood, bimbo feminism and a glossy defiance of patriarchal narratives.

Marketers package these feelings into modular, endlessly adaptable formats. What begins as an expression of autonomy is retooled for maximum shareability and visibility.

Users join in, partly for fun, partly to signal cultural fluency – to show they’re “in the know”.

As participation snowballs, the status instinct takes over. The more visible it becomes, the more necessary it feels to join in and the cycle builds a new kind of pyramid.

The problem is that so much of our culture now runs on this loop. The influencers we anoint as cool have already converted the very things that made them cool into “link in bio” affiliate sales. The subcultures we think we’re joining have been pre-flattened into aesthetic kits, ready for checkout. The films and shows that trade on the spirit rebellion aren’t advancing it - they’re billion-dollar IP machines that strip it for style, drain its momentum and sell the scraps.

There is no longer a gap between cool and capital. The instant something is recognised as desirable, it’s repackaged as a product. Cool now operates as pure capital, and those who hold it often do so precisely because they’ve already traded it in for influence, income, or both. The market doesn’t need to sell us cool anymore - we sell it to each other, hoping each post, purchase or pose might edge us closer to the centre of the feed.